Less than 1% of the estimated $4.5tn global pandemic-induced GDP loss for 2020 is likely to be covered, reflecting pre-COVID-19 coverage exclusions and restrictions as well as the niche character of business interruption (BI) insurance which accounts for less than 2% of the world’s property and casualty (P&C) insurance market.

Commercial insurers have always sought to push the boundaries of insurability by developing innovative and viable approaches to new and emerging risks of major severity such as natural disasters or changes to liability regimes; for example, through alternative risk transfer (ART) solutions.

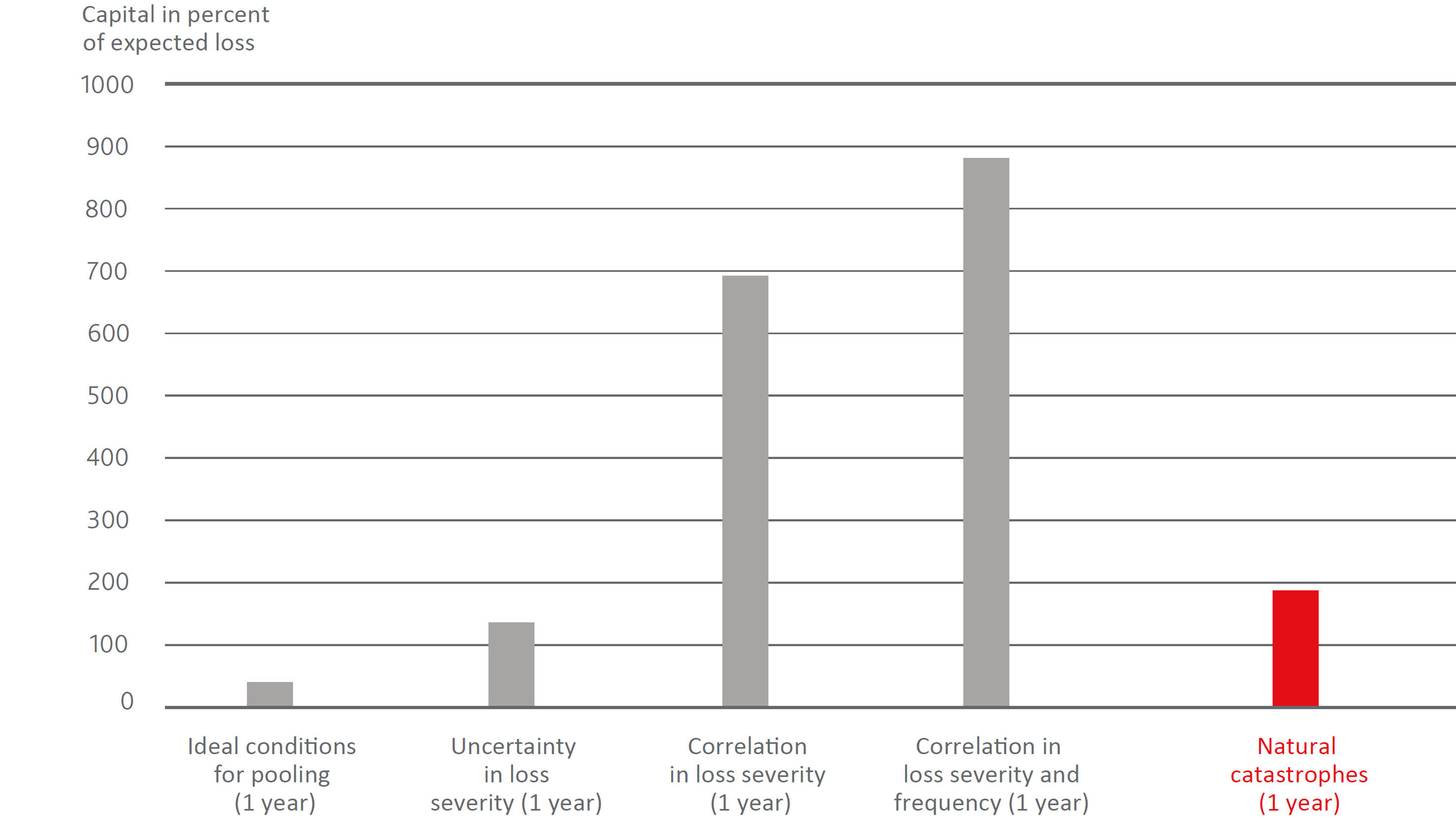

These efforts notwithstanding, pandemic business continuity risk was, in general, never possible nor intended to be covered by the private sector. The shortage of supply primarily results from the high level of embedded risk and, therefore, prohibitively high amounts of capital needed to underpin credible insurance commitments, attributable to the unique correlation in the frequency and severity of pandemic business interruption losses. Coverage for pandemic business continuity risks with meaningful limits, therefore, will remain unavailable from the private insurance market as a result of prohibitively high capital requirements.

Figure 1: Capital requirements (in per cent of expected losses) under various assumptions

|

| Source: The Geneva Association, using the numerical examples of Hartwig et al. 2020 |

Governments need to get involved as ‘insurers of last resort’. There is a broad spectrum of approaches they can adopt in order to facilitate and support the sharing of pandemic risk through partnerships with insurers or stand-alone. The public sector should evaluate insurers’ potential, non-risk bearing contributions to pandemic preparedness and resilience building (e.g. risk assessment, risk mitigation and claims management) and bring to bear its unique ability to organise economically viable risk transfer over time through taxation and borrowing.

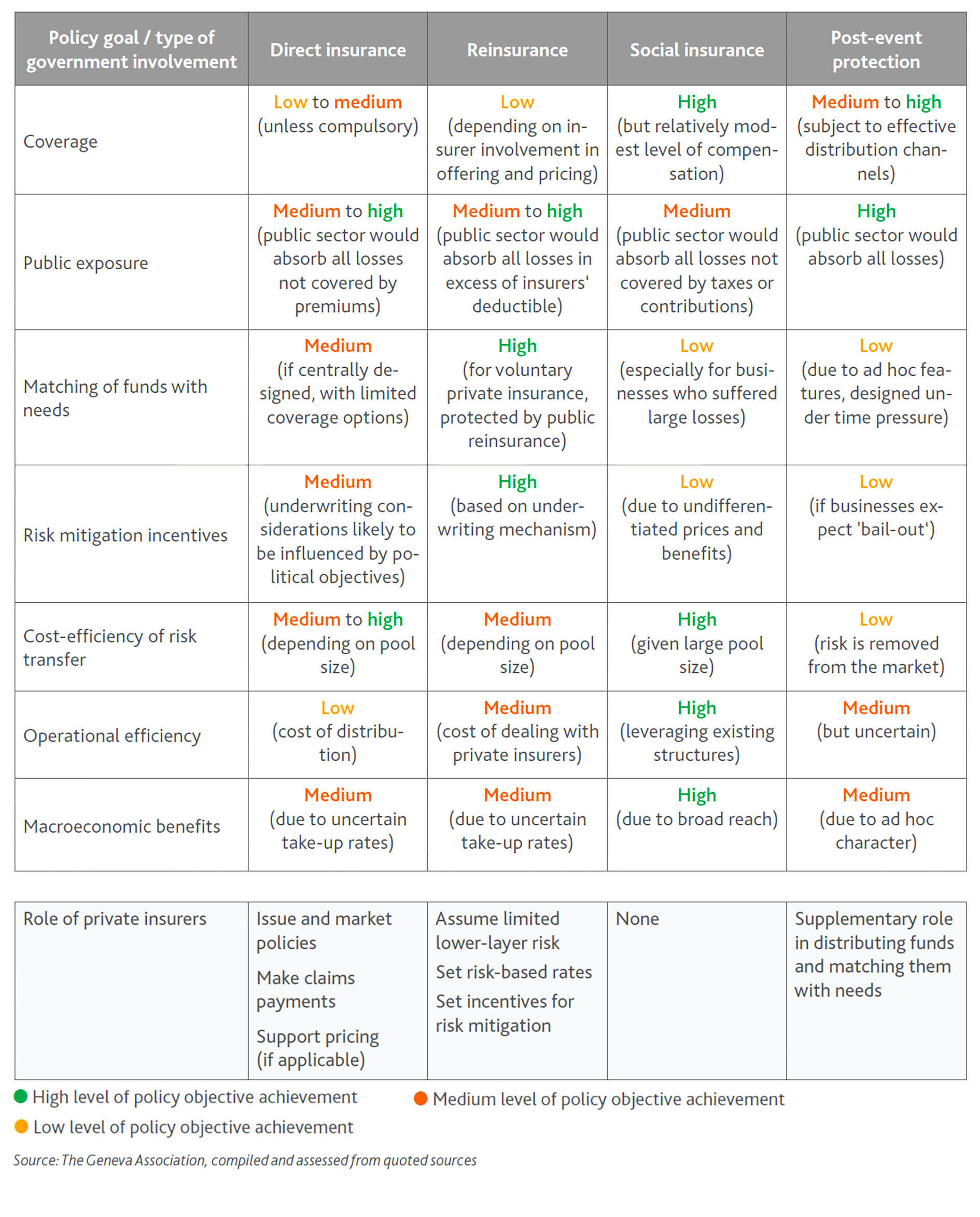

Against this backdrop, one can distinguish between four ‘archetypical’ forms of public-sector involvement in pandemic risk schemes:

- Mandatory or voluntary direct insurance offered by the government and administered by private insurers

Government insurers would not only collect premiums but also be able to borrow funds in case payouts exceed accumulated premiums. The government insurer could market policies directly to insureds or, alternatively, through third parties such as banks, insurers and intermediaries. For claims settlement and payment, the same fundamental options are available.

- Government reinsurance backstopping mandatory or voluntary private-sector coverages

Governments can provide reinsurance to insurers that, prior to a pandemic event, sell pandemic coverage to businesses. The reinsurance coverage would kick in for losses above a certain threshold and up to a designated limit.

- Mandatory social insurance

The distinguishing feature of social insurance is mandatory participation. In the context of pandemic risk, participants would be required to make pre-event payments, for example through a special tax or levy. Benefits from such a scheme would be capped at a relatively modest level of potential losses, in line with the typical objective of social insurance to provide modest coverage for broad segments of the population.

- Post-event financial relief with no pre-event dimension whatsoever

Under this approach the government offers an ad hoc safety net to those impacted by a pandemic. There is no pre-event financing nor pre-event commitment on how funds would be allocated. Those funds are borrowed, transferring the cost burden onto current and future taxpayers. COVID-19 was handled by most governments using this post-event approach to protection.

Table 1: A comparative assessment of four exemplary types of government involvement in pandemic risk funding1

|

| 1 The assessment criteria do not carry the same weights. Arguable macroeconomic benefits and risk mitigation incentives are more relevant overall than cost and operating efficiency, for example. |

We can judge these exemplary types of involvement against their relative strengths and weaknesses in achieving seven specific public policy goals:

- maximum coverage,

- limited public exposure,

- funds matching needs,

- incentives for risk mitigation,

- cost-efficient risk transfer,

- operational efficiency and

- macroeconomic benefits.

Distributing cash post-event is probably the least effective approach, foregoing any benefits from pre-event risk mitigation and preparedness measures.

A consideration for all conceivable options for government involvement is whether the cover should be mandatory or voluntary. This will determine the size of the risk pool and, therefore, the scope for fair risk redistribution. The government would provide the underpinning support to those who have taken out pandemic insurance, and yet it would also have to prop up ‘free riders’ with no insurance. For pandemic systemic risks, where the cover would need to involve a full government guarantee, the mandatory participation of businesses might be most appropriate. Except for the post-disaster relief option, each of the types indicates a valuable role for the insurance industry to play, as absorbers of limited risk, professional distributors and claims managers and/or experts in risk assessment, mitigation and prevention. A

Dr Kai-Uwe Schanz is deputy managing director and head of research and foresight with The Geneva Association.